Project Descriptions

Paintings

Forbidden Aesthetic, Acrylic and Graphite on Canvas, 55 x 104″, 2018 (Passages)

Between 2017 and 2019, I developed a painting series titled Passages, which consists of nine large-scale (ranging from 4 x 9.5’ in length) and six small-scale paintings. Between 2019 and 2021, I am creating a painting series titled Eclipse, which will consist of two large-scale multi-panel pieces (6 x 40’). Both of these series share the common theme of myth.

Passages depicts the complex intertwining between ancient myth, social integration, boundaries, and rites of passage. In this series, folklore busts of mythological gods juxtaposed with abstraction and imagery of contemporary architecture, gardens, and people are all part of my investigation of other-worldly presences and the continuity of Greek myths in current times.

In Eclipse I will investigate themes of old myths, including hubris, humility, and hypocrisy to evoke discussion around the dark aspects of unseen forces and the human psyche. This series probes the junction between the actions of humans and their gods. Reoccurring archetypes of hybridity portrayed by Minotaur and Sphinx function as visual metaphors for the stranger and contradiction.

Stories are powerful tools because they inspire hope, ease human suffering, and can sustain societal order. Centered on the journey of a fictional character, tales serve as a metaphor for the trials of human experience. Plots, acts, formulas, and information about a protagonist and an antagonist reflect the flaws and triumphs of humanity. Old stories, such as Greek myths, occasionally became manifest within organized religions that articulated powerful tools to weigh human acts with ideal measures of virtue and advanced notions of dualism between good and evil. If understood metaphorically, stories can mitigate pain, incite healing, and lead to transcendence. Tales also encouraged self-discipline and courage in challenging times.

In Greek myths, gods often resemble their human counterparts; they were unpredictable, compassionate, just, or destructive. Mirroring the dark aspect of the human psyche, ancient gods expressed rage, betrayal, jealousy, greed, vanity, and pride. In order to express the complexity of human conflict, Homer’s Iliad proposes that not only human pride but also interference by the gods led to the destruction of the city of Troy.

Aphrodite could stand the battle no longer, and Paris’s life was a sacrifice she would not allow … and then she struck, hiding her beloved behind a wall pulling him to safety. Menelaus looked on in amazement, so close he had come after all these years to reclaiming his bride, and here the gods took them as their playthings, changing the course of fate, of mortal lives on a whim. He cried out in rage, a call that was heard by the rest of the gods, and which opened up a wound that would not be healed until the end of the war.[1]

The Iliad is about tragedy, specifically about the relationship between humans, whose hubris is a weakness, and gods, who falter when they behave in an anthropomorphic way.

Many artists have borrowed themes from Greek mythology: for example, Botticelli, Titian, Waterhouse, and John Singer Sargent. Recent art exhibitions featuring artists and their relationship to ancient myth stories have included Rodin and the Art of Ancient Greece at the British Museum, London, UK (2018), and Picasso and Antiquity, Museum of Cycladic Art, Athens, Greece (2019). Occasionally, antiquity themes have served as a metaphor for modern political issues. As described in the exhibition catalogue Picasso and Antiquity, “From the time even when he painted plaster casts of ancient sculptures, Picasso was fascinated by various themes of Greek mythology, issues that distract the trivial or that state of the conflicting impulses of man. Among them, the Minotaur, a Dionysian creature, half man and half animal, emerged as a symbol of the darkest aspects of the human soul and the contemplation of war.”[2] Picasso’s painting Guernica depicts a rampaging bull with a Minotaur temperament, embodying the destruction and chaos that ensued in his native country during the Spanish Civil War.

Fascinated by history, the human condition, culture, and identity, I am compelled to research how ancient myths continue to educate people about the human psyche and how this might influence current events. My previous projects Catalyst and the Silver Road, investigated sustainability of oil and water. Building on these, Passages uses myth as a tool to disseminate topics that encompass land and people. This project is composed of fifteen paintings (nine large, six small) and fifteen small drawings. Two solo exhibitions featured this work: one at the Tinos Cultural Foundation, June 13–July 7, 2019, and the other at Vorres Museum, June 24–July 14, 2019. A second series titled Eclipse (2021) is in production. While both projects share the common theme of myth, Passages hypothesizes the existence of myth gods in a contemporary context, whereas Eclipse investigates the relationship between humans, myth gods, and their stories.

[1] Doty, William G., 2013 Myths & Legends (Pg.204) Flame Tree Publishing, Fullham, London, UK. In Homer’s Iliad, gods, goddesses, and minor deities the gods fought among themselves to wager the outcome of the city of Troy.

[2] Stampolidis, N.C., Berggruen, Olivier. 2019. Picasso and Antiquity, MCA Publication

We will try for the best.

And the more we try, the more we will spoil,

we will complicate matters till we find ourselves

in utter confusion. And then we will stop.

It will be the hour for the gods to work.

The gods always come. They will come down

from their machines, and some they will save,

others they will lift forcibly, abruptly

by the middle; and when they bring some order

they will retire. [1]

The ancients did not see themselves as polytheists. “Their myths were stories to help them explain natural phenomena, and the big questions of life such as where do we come from and where are we are going after death.” [2] This poem by Egyptian-Greek poet C.P. Cavafy [3] narrates how humans make errors and gods intervene selectively to bring about order. I build on this idea in the Passages series by asking what these imperfect ancient gods would do in modern times. How might they inform issues around boundary, diaspora, poverty, equality, and other sustainability-related topics?

Artworks from Passages [4]

To make the paintings, I used photos collected on three trips in Europe. First, in 2016 at the Vorres Museum in Athens, Greece, where I documented the architectural gardens, while I was an artist in residence. Second, in 2018 in London, England, where I visited the exhibition Rodin and the Art of Ancient Greece at National Gallery. Third, in 2018, in Bath, England, where one of England’s oldest Roman sites contains classical sculptures, including Minerva (Athena). In this respect, Passages addresses how Greek archetypes transcend cultural boundaries. Despite vastly different contexts, folklore icons share “world myths” – or at least themes and archetypes that repeat and share motifs, that is, structures that surface across many cultures. [5]

The lush grounds, sculptures, and architecture of the Vorres Museum, and its proximity to Athens, made this an ideal place to explore the complex intertwining of ancient characters and current events. The complex geographical, economic, and philosophical positioning of Greece presents a unique ideological paradigm to investigate. Considered the gateway to western society, it is not only the epicentre of storytelling but also the birthplace of philosophy and democracy. Despite a rich cultural history, Greece is also a place of contradictions. Its geographical location complicates the debate between its openness and boundaries. In the midst of a financial downturn and recent wildfires, Greece remained open in its humanitarian approach to welcoming strangers who arrived on its beaches. How does Greece maintain financial independence and yet assist the displaced to support equality and human rights? As conflicts in the Middle East curtail, migrants have little incentive to return to their home countries where fractured infrastructures are beyond repair. Trapped in a purgatory state, in medias res, they wait.

While global questions have the potential to unite cultures and countries in an effort to find answers, art has the capacity to open new ways of seeing and thinking about current events and the future. My two solo exhibitions of Passages held in Greece during summer 2019 included an invitation for visitors to participate in research on art and global sustainability goals; they were asked to complete a questionnaire on the role of art, and how effective it may be in disseminating these topics. The Global Community Fund, Vice President Research, at the University of Saskatchewan supported the activities, and in 2020 this research will be made public through a lecture at the Gordon Snelgrove Gallery, University of Saskatchewan, and an essay that will be posted online.

[1] Capavfy, C.P. Man the Myth-Maker (1979, 1981). Poem translated by Rae Dalven. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc., Toronto, Canada.

[2] Pizanias, Caterina. 2019 passages / περάσματα, Catalogue Essay, Kostopolous Printing, Athens, Greece.

[3] Contantine P. Capavy was an Egyptian, Greek poet (1863-1933) whose works referenced Greek history, myth, and culture.

[4] Pizanias, Caterina. 2019 passages / περάσματα, Catalogue Essay, Kostopolous Printing, Athens, GR

[5] Doty, William G., 2013 Myths & Legends, Flame Tree Publishing, Fullham, London, UK

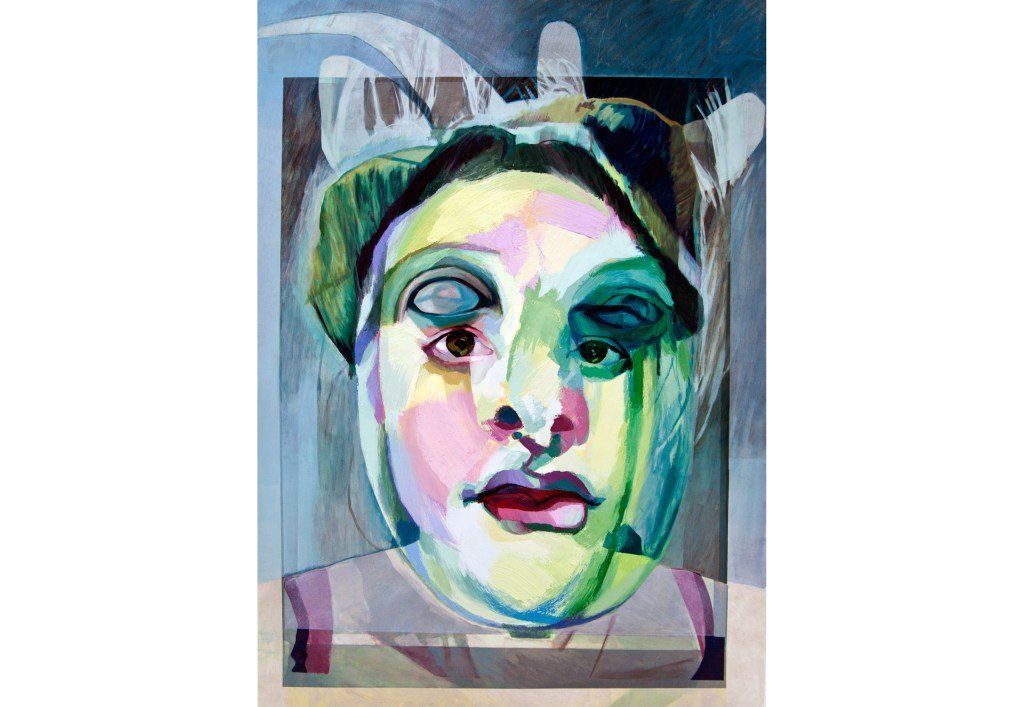

Satire (Self-Portrait with Crying Aphrodite), Oil and Acrylic on Canvas, 51 x 71″, 2019 (Eclipse)

The title Satyr, refers to the role satyr plays in traditional Greek tragedy. The character of a satyr, hideous and comic, addresses the audience by describing a protagonist’s hubris. To develop the painting, I took an image of the Crying Aphrodite (sculpture, Acropolis Museum, Athens, Greece) and layered it over an image of myself. The combination creates a hybridity, hideous as a satyr character. I chose the Crying Aphrodite’s because of the oxidization of bronze in the left eye; residue of bronze is streaming down the left cheek. This coincidence is interesting, and the dual portrait may engage topics around hubris, catharsis, and an unknown boundary between humans and the gods.

Eclipse (2019–2020)

Strong coincidences exist between my artistic practice and my life. Between 2012 and 2016, I developed two painting series (The Human Animal and Catalyst), under the title of Allegory, which shared the common theme of conflict. In his catalogue essay Catalyst, Curator George Harris used the analogy of film structure to describe a synthesis between the objective of my imagery and the real-life events that followed. He states, “Something often happens in the first few minutes of films that prefigures a disaster, which by the end of each film is deployed to catastrophic effect. The act of making The Human Animal (first series produced) seemingly prefigured a real-life catastrophe (later depicted in Catalyst). Keeping form with many disaster movies, the cause of Glenn’s calamity remains out of sight (in The Human Animal); nevertheless, we see its effects (in Catalyst).”[1] As with the Allegory project, I intended to carry out Passages as a one-project endeavour. Similarly, while completing this work, I experienced a real-life event that initiated the next body of work.

While fastening the last canvas of Passage (Forbidden Aesthetic, featuring Aphrodite, goddess of beauty and creativity) to its stretcher, an industrial staple went astray and shot into the pupil of my left eye. Foreshadowing my own Greek tragedy, the evening before the accident I had spent in a vineyard surrounded by mountains, populated by snakes and goats. In the first act of a Greek tragedy, a satyr (half human, half goat), the companion of Dionysus (god of wine), in a drunken stupor unveils a weakness – a mistake that leads to the protagonist’s downfall. Luckily, my story included a miraculous surgeon in Athens who restored my vision. However, for two weeks, I was blind from a trauma-induced cataract. In that time, I was inspired to explore the shadow aspects of Passage. What did I miss? I decided to examine myth, this time from a less altruistic human vantage.

In darkroom of your eye the moonly mind

somersaults to counterfeit eclipse;

bright angels black out over logic’s land

under shutter of their handicaps

commanding that corkscrew comet jet forth ink

to pitch the white world down in swiveling flood,

you overcast all order’s noonday rank

and turn god’s radiant photograph to shade. [2]

Throughout her career American poet, Sylvia Plath, explored mythology and later the occult, as exemplified by this poem. Here, in her poem Sonnet to Satan she describes the event of a solar eclipse as an unseen force. Borrowing from this idea, Eclipse is both a metaphor and title for my forthcoming project. How do mythic stories reveal the dark aspects of unseen forces and the human psyche?

While the focus of Passages was to explore myth and its relationship to boundaries, diaspora, rites of passage, and sustainability, Eclipse will go deeper and investigate the complex boundary between humanity and mythic gods. Questions I might ask include, what are the underlying truths about humanity that empowers us to create without considering consequences? How do these creations lead to error? How do old myths inform us about humanity’s fear of change? For example, if the myth gods encompass the shadow aspects of ourselves, what would they really have to say about globalization and sustainability? This project will focus on lessons around hubris and hypocrisy.

Neil Gaiman’s fiction novel American Gods is set in an America where multiculturalism has led to an infinite number of gods, whose power increases with their popularity, which means they continue to exist. The book narrates a protagonist’s journey with gods in North America (indigenous ones and those brought by immigrants). The old gods contend with the new – technology gods (Tech, New Media and Mr. World (internet)) for attention from humankind. Using this fictitious story, Gaiman asks if new belief systems lessen the power of the existing ones.

Historian Yuval Noah Harari writes in Sapiens (2014) that myth is a human creation, manifested for a variety of reasons, and that myth has enabled humans to evolve as the dominant species. He equates myths with beliefs and value systems. Presenting a compelling case that humans are responsible for creating myths, Yuval urges readers to be more thoughtful of the range of myths we have created, such as corporations, public policies, and systems such as mathematics and accounting. He also describes how myths enable humans to advance, but warns that a lack of ownership (of our creation of those myths) could lead to our demise: “Seventy thousand years ago, Homo sapiens was still an insignificant animal minding its own business in a corner of Africa. In the following millennia, it transformed itself into the master of the entire planet and the terror of the ecosystem. Today it stands on the verge of becoming a god, poised to acquire not only eternal youth, but also the divine abilities of creation and destruction.” [3] In response to this, I ask, is humanity ready to take responsibility for all its creations, including its myths (human-developed systems, honoured as unchangeable) and are we capable of reconsidering our creations, beliefs, structures, and systems, such as public policies and borders?

The Eclipse series is in progress. Following a preliminary drawing sketch stage, I may transform these drawings into large paintings that combine drawing and painting, or I may produce a drawing installation. Currently, the project encompasses three themes and includes one portrait and two works that will consist of four or more connecting panels. The following descriptions provide further detail about my ideas.

Ideas in Progress

The Messenger (mural, multiple panels with spaces between subject matter)

Based on the mythological tale of Daedalus and Icarus, Herbert James Draper’s romantic painting Lament for Icarus depicts a wax-winged Icarus after his tragic fall. Draper’s painting depicts the moment Icarus has fallen from the sky. It is a cautionary tale about youth, overconfidence, emotion, and carelessness. From the perspective of the father – Daedalus – the myth story is about the danger of going too far with creation. Daedalus’s inventions – the maze for the Minotaur and his son’s wings made of wax – led to his own entrapment and loss. My sketch for The Messenger juxtaposes a sequence of birds, thread (as communication), spindles (as eyes), hands weaving (as the fates), architecture, Aphrodite and Rodin sculptures (gods debating), taxidermy wings from doves and magpies.

Minotaur: The Warning

Preternatural and arcane, the story of the Minotaur has held enduring appeal for artists, perhaps because its core themes – forbidden desire, the craving for satisfaction, and the basic fact of sexual peculiarity – are all too real, discernible everywhere amid the trivia and neurosis of modern life. [4] As a metaphor for unruly, bullish, primal behaviour, the Minotaur represents the animal within us. In the Greek myth, Poseidon curses Pasiphae (daughter of Helios, the sun) to mate with an ox. She gives birth to a Minotaur, who is a hybrid of human and bull. In a maze designed by Daedalus, the Minotaur dies by being slayed by Theseus. Artists such as Picasso anthropomorphized the Minotaur as himself, or used it as a metaphor for the aggression of the Spanish civil war in the print series Vollard Suite. [5] My preliminary sketch for Minotaur: The Warning is an expansion of the original Sphynx painting (from Passages) and includes a gate and graffiti: a motif for communication, negotiation, and rite of passage. As hybrids, the sphynx and Minotaur share similar biological disposition (half-human–half-animal), yet occupy opposing roles of power. Athena and her Pallas – a dark psyche companion that protects cities, will function as a visual metaphor for uncertainty.

[1] Harris, George. 2018. Curatorial essay for Catalyst, Two Rivers Gallery, Canada

[2] Plath, Syliva. Sonnet to Satan, Poem #30, Plath mss II, Box 15, Publications Scrapbook, Lilly Library Archives, Indiana University at Bloomington, USA (Pre 1954).

[3] Harari, Yuval Noah. 2014. Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind (p. 415). Signal (McClelland & Stewart, UK)/Penguin Random House, Canada

[4] Cahill, James. 2018. Flying Too Close to the Sun: Myths in Art from Classical to Contemporary, The Monster in Maze – Theseus and the Minotaur (p. 41). Phaidon Press Limited, London, UK.

[5] Picasso developed 100 etchings (printmaking) from 1930 to 1937 That were commissioned by the French art dealer, Ambroise Vollard.

Burning Tree, Oil and Acrylic on Canvas, 50 x 76″, 2017 (The Silver Road, 2017)

The Silver Road

How do communities in arid climates survive without water?

This is a project exploring the challenges of water sustainability, abandonment and how a remote community struggles to sustain and rebuild despite desertification. This project was initiated during an artist residency at Joya: AiR in the arid national park of Sierra María-Los Vélez, Spain in December 2015.

Home, Digital Photograph, 7 x 8″, 2017 (Gold Dust)

Gold Dust

How does migration and shifting populations impact the natural environment?

Uranium City once boasted a population of 5,000 residents who worked in the uranium mining industry and was a thriving community until the 1980s when the mine closed down. Today, it looks very different – all but 50 residents remain. Most homes, businesses, community institutions such as the legion hall, the indoor hockey rink, the high school have been left behind, abandoned. The remnants of community are recognizable, and timely enough to evoke questions around abandonment, the flux of community around singular natural resources, responsibility, and how migration and shifting populations affect the environment.

Studio Image, Catalyst and the Human Animal

Allegory

Between 2012 and 2016, I developed two painting series under the title of Allegory, which consists of 17 large-scale paintings (ranging from 48 x 86”). The two series share the common theme of conflict.

Catalyst (Series 2)

In June 2012, my partner and I discovered an oil spill under our house. By highlighting this personal experience, the paintings offer insight into the psychological impact of contamination and the deeper meaning of how people relate with the environment.

Description

In the event of an oil spill on the ground or underground, compounds can migrate through the soil, contaminating it; penetrate a cement floor; permeate into a house, polluting the air; and seep into wells, poisoning the drinking water.

For example, if the soil beneath a structure is contaminated, hydrocarbons can permeate the foundation, and move up and into the insulation, drywall, new hardwood floors, a favorite bureau, a new couch, and even a coffee maker. Once they have entered an object, they off-gas for many years. Even though the air may seem clean and there is no visible evidence of oil, a site can be toxic with carcinogens, and essentially poisonous—with serious consequences for human health.

In 2012, when we discovered a substantial oil spill beneath the foundation of our house,renovate, nest, and create memories within this first home were put aside to address the reality and complexity of being tethered to catastrophe.

This event propelled me to develop the Catalyst series, which narrates moments of my journey and my partner`s with the contamination and remediation. It also offered a platform to address the universal topic of oil and what it really means for those who live in proximity to sites that pose similar risks.

Cave 1 and The Human Psyche

One of the paintings, entitled Cave 1, depicts my partner collapsing over the excavation pit, which appears rugged, foreboding, and cave-like, while his body language suggests anger, defeat, and acceptance.

This painting was one of two selected to exhibit in the international art exhibition Art@tell in St.Gallen, Switzerland, in 2014. The curator, Deborah Keller offered insight about the project by stating that the paintings remind us of our abuse and our questionable handling of natural resources (i.e., fossil fuel) and refer to the interpretation of house as a symbol for the human psyche (as we know it from psychology, literature, and philosophy).

In her essay In the Wake of Dualistic Imagery for the catalogue published for the exhibition at Karsh Masson (Ottawa, 2015) Deborah states that “the house as a leitmotif of the series plays an important role by addressing collective memories and emotions. Psychology, philosophy and literature have all at times cited the house as a symbol of the human psyche. In this interpretation, the underground is attributed the role of the unconcious, where according to Freud the uncanny arises. In several works from the series, such as Cave 1, Cave 2 and Crimson Lake (Home), the viewer is confronted by this part of the house or even themselves in a threatening way. The protection and security that are generally associated with the home seem completely abolished – the building is eroded, destroyed, or even bleeding. Other paintings from this series, such as Demolition Tea Party, depict a celebration or social gathering. It is contrasted with in an inverted image of a demolition site to juxtapose celebration with deconstruction. My intent with this image was to address how an individual can struggle with trauma, but must put it aside to participate in the pleasures of life.

A second read may suggest a ‘conflict’ between the female figures at the table. This is affirmed by the deconstruction of the landscape in the background. In using the term Tea Party in the title, I suggest it could also be a moment of protest. Crimson Lake (Home) was developed from a photo that I took of my former home, exposed and teetering on stilts. To address the environmental impact I depicted it above a tree landscape with a gap or a mirror reflection in the area below which is lake-like. The colour of acid green and red offers creates an uneasiness and is menacing, symbolizing a hidden danger.

Deborah addresses these two additional works by stating “The visualization of this ‘small-scale’ pollution refers inevitably to the larger global context. It compels us to consider our questionable use of oil, a non-renewable resource, and our exploitative attitude toward nature. For the viewer this attitude is most evident in the work entitled Caught in a Tailings Pond. The complex entanglement of the individual within the mechanisms of the oil industry and their collective impact is presented here in a simplified but symbolically powerful image. It is also this image that makes visible the personal motivation of the series, because the person who is in danger of being choked by the wake of toxic residues is the artist herself.” (Catalogue Essay, Karsh-Masson 2015)

This project reveals details and the personal impact of the contamination of my home. In doing so, it not only acknowledges my personal journey but also raises awareness for those who seek to know more about environmental risks, taking the work to a more universal level. This project may also offer insight for those who live in proximity to oil and gas development and transportation sites and who might question, “what would happen if…”

Panel 1, Oil on Canvas, 68 x 85″, 2013 (The Human Animal)

The Human Animal (Series 1)

Series 1, The Human Animal, is about politics and primal instincts. Animal symbols represent the fight-or-flight instinct, and a repeating motif of a graffiti wall functions as a visual metaphor for divisions: keep out and protect those within.

Description

This series is structured with pictorial links between the images to signify a narrative structure (introduction, climax, and resolution). The project offered a unique opportunity to reflect on communication strategies, sign, and how multiple images can reflect a sense of time. The paintings are not illustrative but are intended to be interpretive. They contain metaphor and symbolism, which allow the viewer to formulate details of the story or event.

In developing the project, I thought about the complexity of social dynamics, politics, and primal instincts. I am interested in the theme of human conflict initiated by emotional, primal instincts to protect identity and common values. In terms of content, I depict a battle between people elicited by primal instincts. So, in the first image I portray wolves and deer in front of a riot crowd, to represent an animalistic, primal instinct of fear or flight; this image introduces the viewer to the “atmosphere” of story, similar to the introductory scene of a movie. In the third painting (top panel) I borrow a classical frieze composition to depict people in front of a graffiti wall. The wall, a visual metaphor for division—both keep out and also protect those within—can be interpreted as symbolizing the evolution of conflict. The fifth painting represents a judgement. Two figures wear gas masks with jackal ears to symbolize the Egyptian myth character Anubis. The Egyptians once believed that in death you are met by Anubis who conducts a “weighing of the heart”. In this image, they gaze at the viewer through a mirror reflection. The legs above offer the audience and opportunity to participate in the judging of the crime. The final scene is a condemnation. This panel features two figures with large bones or a gaping mouth (dinosaur rib cage is set over a group of collapsed bodies). The mouth symbolizes the mythological creature Ammit whose job is to consume the heavy hearted. This scene represents their ill fate. By showcasing primal behavior—not often associated with civilized society—this project highlights connections to the primal self and offers insight into the complexity of contemporary events and conflicts.

To inform my compositions and effectively capture these ideas in single-shot images, I expanded my knowledge of body language by studying highly choreographed films such as The Godfather (Francis Ford Coppola, 1974), Blow Up (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1966), and also documentaries of stage plays such as Mozart, and Il Re Pastore (2007).

The Vistula, Opposing Forces (2 of 3 panels), Oil on Canvas, 40 x 79″, 2010 (Cracovia)

Poland is a rare example of a preserved traditional culture, unique for its dark history, remote location, and exclusive language. With the joining of the European Union in 2003, it has faced the complex balance of maintaining old values with western influence.

In the fall of 2005 I relocated to the city of Krakow, to research a project which would depict the life, culture, and the people of contemporary Poland. This body of work is entitled Cracovia and is composed of sixteen figure narratives and cityscapes. The project was first initiated in the district of Kazimierz, The Old Jewish Ghetto, during an eight-month residence. The series guides viewers through post-communist Poland, shedding light on historically loaded areas of Kazimierz, the Old City, and its people. My approach was to create a ‘documentary’ that would record Krakow today by contrasting the strikingly historical backdrops with youth in contemporary clothing in everyday contexts.

When developing this project I was interested in Poland’s unique struggle to balance the emotional burden of its horrific past with its modern existence, as this is an intrinsic element to Poland’s contemporary identity. By offering an informed, objective image of contemporary Poland I wanted to provide a neutral dissemination of the political, ideological, and theoretical issues which have greatly influenced post-communist Eastern Europe. This work opens a dialogue about history, culture, and the procession of time. It is my hope that it also provides insight to a culture that for many North Americans, may be far removed.

Drawings

Residencies stimulate my creativity and lead to challenging discussions, new processes, a re-assessment of ideas, or help me imagine new projects in a much bigger way. This project was first initiated during a two week artist residency Joya: AiR located in the national park of Sierra María-Los Vélez, Spain in December 2015. The region is most known for its arid climate and challenges with water sustainability. Many landowners have abandoned their farms and countless remnants of homes scatter the fields within a five mile radius of the residency building. Most of the drawings in this exhibition were sketched on site.

The exhibition Tertium Quid presents an installation of thirty-five drawings on paper. These include twenty preparation drawings from the projects Catalyst and The Human Animal that share the overarching theme of conflict. The Catalyst series explores the psychological impact of the artist’s personal experience of oil contamination in her home and also deeper meanings of how people relate to the environment. The Human Animal series highlights primal behavior, connections to the primal self, and the complexity of contemporary events and conflicts.

The title of the exhibition, Tertium Quid, refers to an unidentified third element in combination with two known ones. In the early twentieth century, tertium quid described innovations in film editing, specifically when film director Sergei Eisenstein applied his montage theory in Battleship Potemkin (1925). To create the Odessa Staircase scene, Eisenstein combined both focused and zoomed-out viewpoints to elongate the perception of time. He then sped up or slowed down these shots to generate intensity. Many scenes focused on the faces of the protagonists, offering the audience an immediate emotional connection to the characters. These techniques continue to be applied in motion film and have been expanded to other artistic mediums such as illustration, animation, and graphic novels.

Inspired by montage theory, the Tertium Quid installation employs framing devices and spacing considerations to generate a sense of time. The thirty-five drawings are also assembled and juxtaposed to widen the possibilities of engagement and semiotics. The intent of the project is to evoke the question: What conceptual outcomes occur when one image is juxtaposed with another? To assist the viewer on this journey, the narrative imagery includes symbolism, metaphor, and signs. Each fragment offers insight into the complexity and continuum of the story, luring the viewer into both the abyss of catastrophe and the fortitude of resolution

I make many drawings to understand what I am looking at, simplify mark making, and understand the underlying structure of the form. If I choose to include a figure in an image it requires much precision. The audience may be hardwired to recognize a human form in the most abstract shape but can also quickly detect errors or deviations, particularly in a realistic rendition. In order to inform my figure drawings and paintings I develop bone, muscle, and topographical studies. Rarely have I found the exact rendering of a position I need in anatomical book, so these personal studies are done using a variety of books, a skeleton, and memory. A muscle sketch of a position can offer me deep knowledge of the surface anatomy “map” that I refer to throughout the figure painting process. The more figures in a painting, the more preparation drawings.

2010 President’s SSHRC

Since my teaching appointment in 2009, I have been actively investigating ways to integrate new disciplines and technologies to my practice, as well seeking areas and opportunities for interdisciplinary research. In this regard, securing a president’s SSHRC grant in 2010 enabled me to research the human anatomy. The intent of the research was to develop an ability to visualize the anatomical structure beneath the skin and improve my understanding of the relationships between bone and muscles. This translated into a better and more informed representation of the body in my work, and I was able to bring a distinctive technical skill to the Department of Art and Art History. The research project involved three components: (a) anatomical lessons and laboratory sessions with Keith Russell and Chantal Kawalilak, College of Kinesiology, which provided first-hand insights into the topic; (b) travel to Florence, Italy, to visit the Specola Museum, as well as other prestigious museums, to view a large and rare permanent exhibition of anatomical wax sculptures; and (c) live model drawing sessions. As a result of this project, I created large body of unique drawings that unite the underlying skeletal and musculature systems with formal modelling of the figure. This project also strengthened my ability to communicate and teach anatomy, which has been useful not only in the development of my paintings but also in teaching Art 212.6 (second-year drawing), which features a section on anatomical drawing. I have continued to use anatomy to inform my figure work.